history

dem likkle

but dem tallawah

nothing

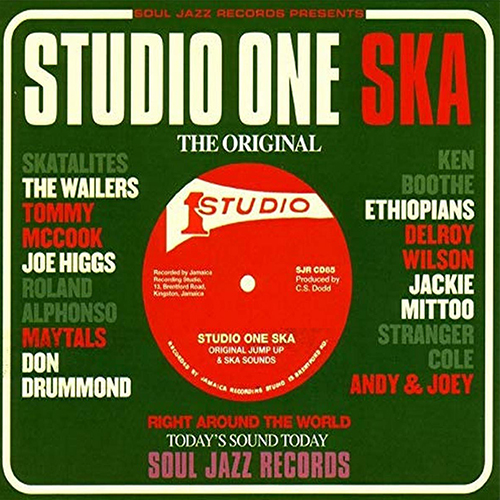

from ska

to dancehall

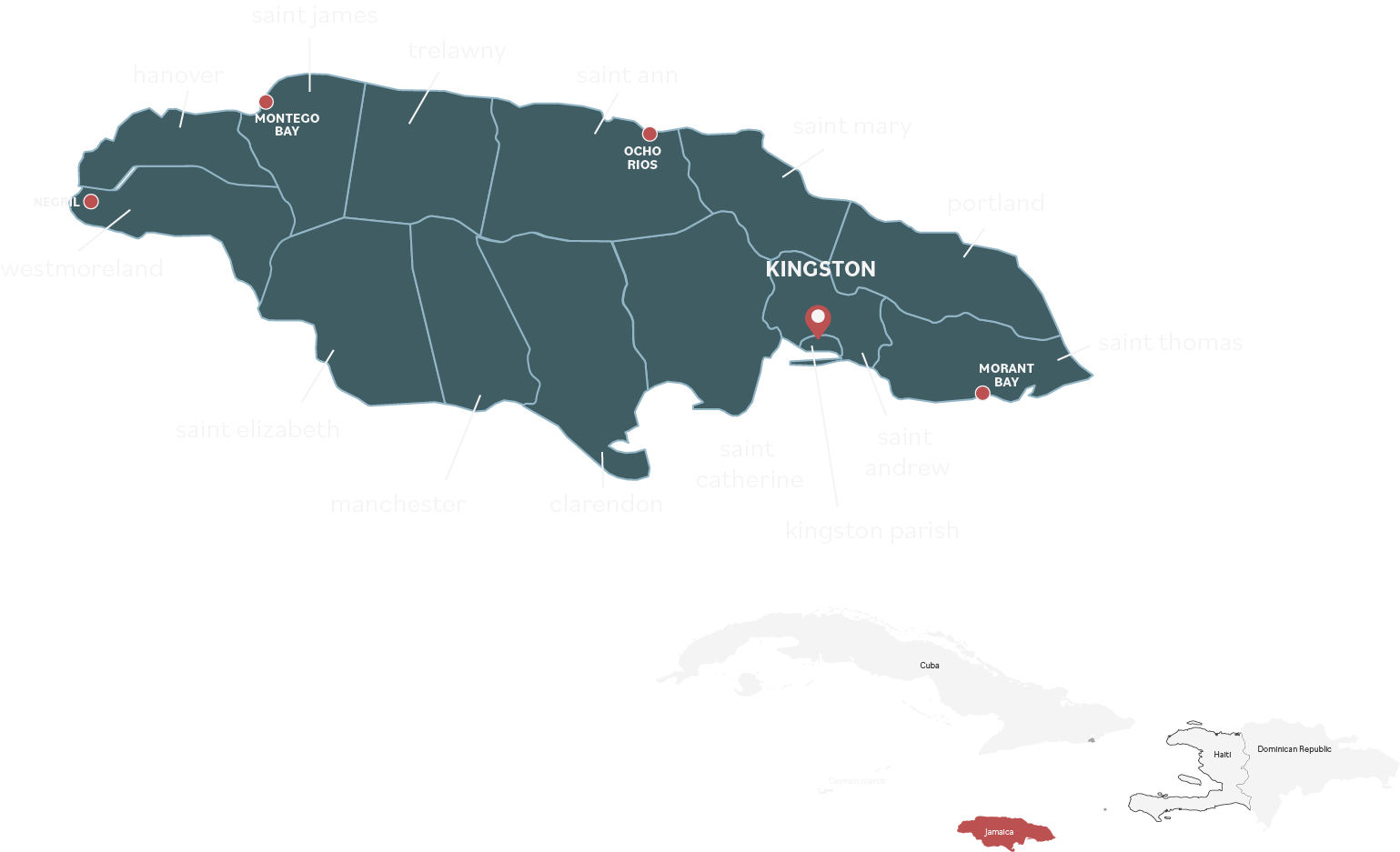

The following timeline is intended to provide a concise overview of the history of Jamaican Popular Music (JPM). Of course, genres and cultural developments cannot be tied to dates. Nevertheless, this provides a chronological and compact overview that highlights the musical forms and cultures that are ultimately all reflected in the Reggae Revival.

This timeline is limited to popular musical forms of Jamaica. The country has a rich and very interesting history of traditional and pre-popular music forms that reflect the history of the country and its many different (brutally enforced) cultural influences. – From Kumina to mento. For more information on this, the works of Jamaican anthropologist and musicologist Olive Lewin are highly recommended.

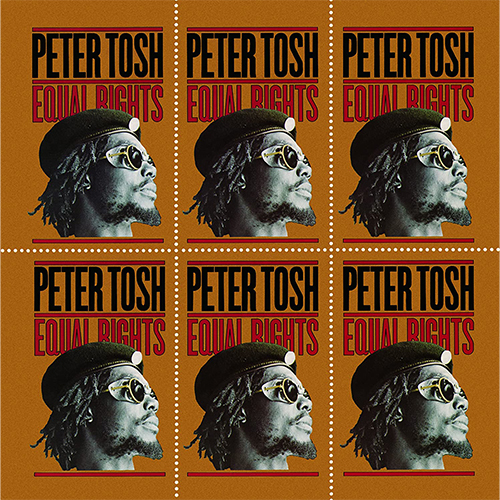

In the 1970s, once more the music became “[…] slower, heavier, thicker, and more complex […]“ (Katz 2012: 139). This music was finally independent from the US-American roots of ska and a purely Jamaican music that incorporated various elements of Jamaica's cultural heritage. What was pivotal was the connection and the commitment of many artistes to Rastafari which was reflected in the music, lyrics and the artiste’s appearance. roots reggae was a music of social protest. Especially Bob Marley and his collaboration with Island Records made roots reggae worldwide popular. ▶

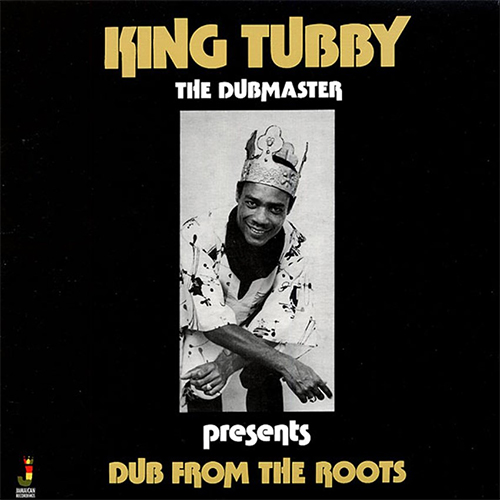

At the same time as roots reggae arose, dub emerged: Producers and artistes like King Tubby, Lee “Scratch” Perry, Sly & Robbie or Augustus Pablo took roots reggae tunes and remixed their single tracks by the extensive use of delay and reverb effects. These newly created tunes then often ended up on the B-side of the records. In a way, the mixing desk became the instrument. Through this manipulation of the music they created big soundscapes and a new sound at all. Dub had an impact on later upcoming styles such as house, garage, trance or dubstep. ▶

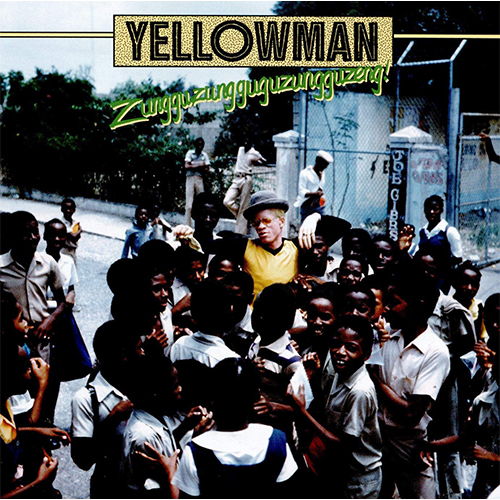

In the 1970s, Jamaica faced a new political and economic situation that often erupted into violence. roots reggae – once emerged as a rebel music against inequality – didn’t have its original status anymore. New technologies like the drum machine and the use of samples came in which brought different approaches in the production of music and finally resulted in a new sound. dancehall turned – as opposed to globalized roots reggae – towards the local Jamaican audience again and represented subculture in contrast to a pop culture. deejays came in and brought the toasting along. Moreover, dancehall was a music that did not work with bands but used the computer as a full instrument to produce riddims. In dancehall, the joy of dancing and going-out was superficial. However, it was slackness – violent and sexual related topics – which characterized dancehall and that was a result of the political and social circumstances. The drugs and gang crime were musically reflected in Dancehall’s lyrics that glorified violence. ▶

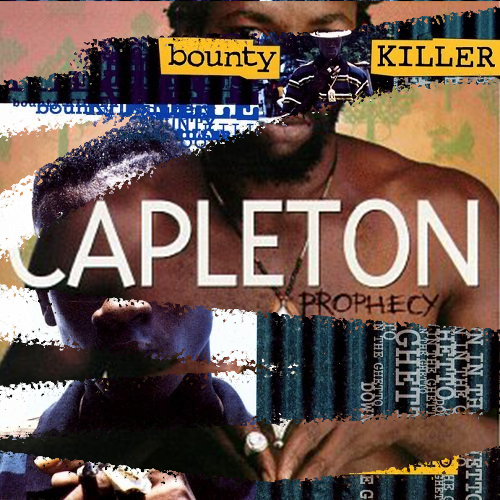

Because of dancehall's partly violent topics, many artistes felt the need for a return of reggae and its positive and socially relevant messages. Artistes like Buju Banton or Capleton embodied this shift through their transition from dancehall-artistes with controversial and homophobic lyrics to artistes who identify themselves with Rastafari and became part of a “Rasta resurgence” among artistes like Luciano or Garnet Silk are numbered. This movement with “positive” and socio-critical contents is also called “conscious reggae”. In addition, there was the re-integration of "real" instruments and a return to more complex musical arrangements combined with computer-programmed drum beats. However, the comeback of reggae did not imply the end of dancehall. Dancehall’s popularity increased and became more and more globalized. So, dancehall and “conscious reggae" existed both side by side. This era is regarded as a first „Roots-“/„Reggae Revival” for which a dissatisfaction with social and musical circumstances was responsible. ▶

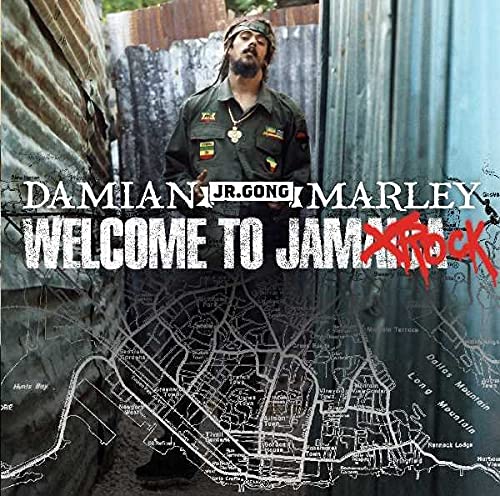

From the mid of the 1990s, many reggae artistes from outside Jamaica appeared on the scene: Gentleman, Seeed, SOJA, Rebelution, Groundation or Dub Inc. are just a few of those who came up at this time or later and who are still present today. At the same time, the number of (today still active) Jamaican reggae and dancehall artistes increased. Popular names are for example Sean Paul, Vybz Kartel, Tanya Stephens, Lady Saw, Bushman, some of the Marley brothers, Tarrus Riley, Pressure and more. In the nearly two decades before the Reggae Revival emerged, a kind of musical parallelism in JPM arose:

"Jamaican popular music can take any number of bewildering forms: hardcore dancehall deejays like Bounty Killer and Movado, […] while artists like Tarrus Riley and Dwayne Stephenson present an updated classical roots […]. Somewhere in between are the fiery Bobo Dread ranters like Capleton and Sizzla […]; forward-thinking females such as Queen Ifrica and Etana take dancehall into new territories […]." (Katz 2012: 417).

recommended literature on the history of JPM

The Rough Guide To Reggae

Steve Barrow

a great work on the history and beginning of jpm and its pioneers up to the 1990s.

Bass Culture – When Reggae Was King

Lloyd Bradley

a great overview of the development of jamaican popular music and especially reggae in jamaica.

Reggae Routes – The Story of Jamaican Music

Kevin O'Brien Chang & Wayne Chen

a book that examines the eras of ska, rocksteady, roots reggae and dancehall and relates the music cultures to the social and political processes in jamaica.

Inna Di Dancehall – Popular Culture And the Politics of Identity in Jamaica

Donna P. Hope

a fantastic insider's work about jamaica's dancehall culture, its sociopolitical relevance, power relations and gender roles.

Solid Foundation – An Oral History Of Reggae

David Katz

a great overview of jpm reaching into the 2010s and based on an incredible amount of interviews.

DanceHall - From Slave Ship to Ghetto

Sonjah Stanley Niaah

an interesting work on dancehall culture, its emergence in kingston's ghettos, and the context of the african diaspora.

Wake The Town and Tell the People – Dancehall Culture in Jamaica

Norman C. Stolzoff

one of the most important works on dancehall culture in jamaica and an excellent introduction to the subject.

Dub – Soundscapes and Shattered Songs in Jamaican Reggae

Michael E. Veal

the standard work on dub culture, its origins, pioneers and importance for jamaica and the world.

The Rough Guide to Reggae

Bass Culture - When Reggae Was King

Reggae Routes – The Story of Jamaican Music

Inna Di Dancehall – Popular Culture And the Politics of Identity in Jamaica

Solid Foundation – An Oral History Of Reggae

DanceHall - From Slave Ship to Ghetto

Wake The Town and Tell the People – Dancehall Culture in Jamaica

Dub – Soundscapes and Shattered Songs in Jamaican Reggae

bibliography

- Bradley, Lloyd. 2001. Bass culture: When Reggae was King. London: Penguin.

- Katz, David. 2012. Solid Foundation: An Oral History of Reggae. London: Jawbone Press.

- Veal, Michael. 2007. Dub: Soundscapes and Shattered Songs in Jamaican Reggae. Middletown: Wesleyan University Press.